The Companies Act, 2013 defines “joint ventures” (hereafter referred to as “JVs”) as a joint arrangement entered into by parties that have joint control over the arrangement and rights to its net assets. The structures and forms of joint ventures can vary widely depending on the objectives, industries involved, and the level of integration desired by the partners.

For instance, in equity-based JVs, a new entity is created that operates independently, with each partner contributing assets or businesses to form the joint venture. In contractual or hybrid JVs, the collaboration involves specific projects or objectives without forming a new legal entity or creating one that ceases to exist once the collaboration is completed. Cooperative joint ventures involve two or more companies coming together to undertake significant projects or research initiatives without forming a new entity. The presence or absence of the parents’ transfer of assets or businesses can vary in JVs, depending on the type of joint venture being created.

Exploring the concept of JVs under the Indian Competition Act

The Indian Competition Act, 2002 (“the Act”) does not clearly state the requirements for notifiable joint ventures (JVs). However, this lack of clarity does not directly eliminate the necessity of notifying JVs to the Indian antitrust agency, the Competition Commission of India (CCI). Parties to a JV transaction often find themselves uncertain about whether their proposed JVs require notification, as Section 5 of the Act discusses the de minimis threshold that exempts certain combinations—such as acquisitions, acquisition of control, mergers, or amalgamations—from notifying the CCI.

The 2023 Amendment introduced the Deal Value Threshold (DVT) provisions into the Act, stipulating that any transaction involving the acquisition of control, shares, voting rights, or assets of an enterprise, as well as mergers or amalgamations, exceeding two thousand crore rupees must be notified. Consequently, JVs that do not fall within the nature of acquisition, control, merger, or amalgamation present a significant question regarding their regulation.

Section 6 of the Act prohibits any person or enterprise from entering into a combination that causes or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition in India (AAEC). According to Section 5, only transactions in the nature of acquisition, control, merger, or amalgamation are considered branches of any combination, thereby excluding JVs.

In light of the above, is it safe to conclude that JVs incorporated or proposed to be incorporated as new entities need not be notified to the CCI? I believe not, because the Competition Law aims to ex-ante determine the appreciable risks of any form of collaboration, including JVs, on competition. In some instances, JVs entered between or among competitors, rather than promoting competition and benefiting end consumers, have resulted in limiting competition. Further, in many cases, it was found that under the guise of JVs and JV agreements, horizontally placed entities were cooperating on price, production, storage, and distribution, collectively limiting competition in the market.

A pertinent question arises as to how we will determine notifiable JVs in the absence of any thresholds or provisions under the Act. The Act is indeed somewhat ambiguous regarding notifiable JV agreements. Generally, the notifiability of JVs depends on their creation method. JVs that do not own assets or generate revenue, called greenfield JVs, are not typically notifiable.

In contrast, JVs where parents contribute existing assets or businesses, called brownfield JVs, may be notifiable if the prescribed financial thresholds under the Act are satisfied. JVs, wherein one or more parties to the combination transfer their business/assets to the joint venture, will be considered like acquisition or acquisition of control, and for the purpose of the de minimis exemption, they would be analyzed under the thresholds given in Section 5 (a), (b), and (c) of the Act.

When would any JV transaction be considered as an acquisition or acquisition of control?

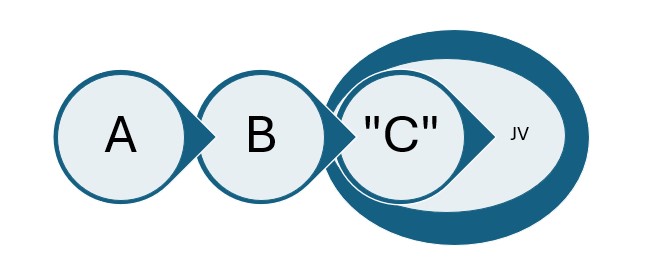

In a scenario where two separate entities, “A” (incorporated in the US) and “B” (incorporated in India), decide to form a new joint venture “C” in India, and in the creation of “C”, “B” transfers its assets/part of its business into “C” and the transaction is such that the “A” and “B” hold equal shareholding in the newly incorporated JV. Further, after the competition of the transaction “A” through “C” will have indirect control over “B. The transfer of assets/part of the business of “B” into “C” will be considered an acquisition by C. Consequently, “A,” though being a foreign entity, will now be able to exercise control over the assets/business of “B” through its equal shareholding in “C”.

In this scenario of cross-border JV, the transaction comprises two interconnected steps.

- Step-1, a transaction where “B” transfers its assets/part of its business into “C”. [Acquisition]

- Step-2, where after the transaction Step-1 “A” exercises control over “B”. [Acquiring of control]

Therefore, in analyzing the de minimis exemption the assets and turnover of “B” and “C” shall be jointly calculated. However, if we assume that this transaction only has step 1, assets and turnover of only “B” will be seen.

CCI 43A Orders Concerning JVs

Order u/s 43A of the Act in the notice given u/s 6(2) by Johnson & Johnson Innovation: The Competition Commission of India in its Section 43A proceedings initiated observed that the notice relating to the formation of a greenfield joint venture (“JV”), to carry out research and development in respect of robotic systems for surgical intervention was delayed and filed after expiry of the statutory time of 30 days and therefore subsequently imposed a penalty of INR 5,00,000 on parties. This combination of setting up green filed JV involved the transfer of certain assets (including intellectual property and related assets) between the parties.

Order u/s 43A of the Act in the notice given u/s 6(2) by Tesco Overseas Investments Limited: On 31 March 2014, the Commission received a notice from the acquirer regarding the proposed acquisition of 50% of the equity share capital, following a Joint Venture Agreement (JV Agreement) and Share Purchase Agreement (SPA) executed between the parties. The Acquirer has received approval from the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) and the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) for the acquisition on 17 December 2013. According to Regulation 5(8) of the Combination Regulations, the acquirer was required to notify the Commission within thirty days of its application to DIPP and FIPB, i.e., by 16 January 2014.

However, the acquirer submitted the notice on 31 March 2014, resulting in a delay of 73 days. The Commission, in its meeting on 17 April 2014, decided to admit the delayed notice under Regulation 7 of the Combination Regulations, while noting potential separate proceedings under Section 43A. According to Section 43A, the maximum penalty for such a delay could be 1% of the total turnover or assets of the combination, exceeding INR 600 crores in this case. Given that the acquirer had voluntarily filed the notice within 30 days of executing the JV Agreement and SPA despite the 73-day delay, the Commission imposed a nominal penalty of INR 3 crores on TOIL.

Order under Section 43A of the Act, 2002 (“Act”) about an inquiry initiated under sub-section (1) of Section 20 of the Act against General Electric Company (“GE”), GE Industrial France SAS (“GEIF”) and GE Energy Europe B.V: On 20 October 2014, the Commission took suo motu cognizance of public announcements (PAs) made by parties regarding their intent to acquire significant shares in two target companies. This transaction included forming three joint ventures (JVs). Agreements for these transactions were executed on 4 November 2014. Initially, the Commission found the notice filed on 24 November 2014 non-compliant with the Combination Regulations, which led acquirers to a fresh notice before the Commission.

The Commission approved the proposed combination, including the JVs, on 5 May 2015, pending Section 43A proceedings. In 43A proceedings initiated against the acquirers, the Commission observed that the Acquirers failed to notify within 30 days of communicating their intent to SEBI, interpreting “other documents” broadly to include unilateral communications like PAs. Despite the Acquirers’ argument that only binding agreements should trigger notification, the Commission imposed a penalty under Section 43A.

Although the maximum penalty could have been 1% of the combined value of worldwide assets (approximately USD 6,953 million or INR 46,000 crore), the Commission, considering the Acquirers’ bona fide intent to file the notice and the non-consummation of the combination without approval, set the penalty at INR 5 crore.

Conclusion

Despite the ambiguity in the Act regarding notifiable JVs, it cannot be concluded that JVs do not require notification to the CCI. Competition Law aims to assess the risks of all collaborations, including JVs, on market competition. The determination of notifiable JVs depends largely on their structure and the specifics of their formation.

Greenfield JVs, which do not own assets or generate revenue, are typically notifiable. In contrast, brownfield JVs, which involve the transfer of existing assets or businesses from the parent companies, may require notification if they meet the prescribed financial thresholds under the Act. For instance, if a JV involves the transfer of assets that results in the acquisition of control, it may be considered notifiable. This is particularly relevant in cross-border JVs where transactions result in one entity gaining control over another’s assets.

The consequences of failing to notify the CCI can be significant. For example, in the case of Johnson & Johnson, the CCI imposed a penalty for delayed notification of a greenfield JV involving asset transfers. Similarly, Tesco Overseas Investments Limited faced penalties for not notifying the CCI within the stipulated time frame for a JV transaction.

Therefore, while the Act may not explicitly outline the requirements for notifiable JVs, parties involved in JV transactions must conduct a thorough analysis under the Act. This involves examining the structure of the JV, the nature of asset transfers, and the financial thresholds to determine the need for notification. Careful compliance with these requirements is essential to avoid penalties and ensure that the JV does not adversely affect competition in the market.

In summary, the notifiability of JVs hinges on their nature, the specifics of asset transfers, and compliance with financial thresholds. Given the complexities and potential penalties involved, companies must engage in careful analysis and seek legal guidance to navigate the requirements of the Competition Act effectively.

…

Contact us at hello@lawgacy.com to feature your firm’s deals, articles, columns, or press releases.